Siren Song: A Character Study

Rule of Rose (2006) is the most affecting study of trauma in existence.

Trigger warning for discussions of child sexual abuse, self-harm, abortion, and animal cruelty. Spoilers for almost the entire game.

I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each.

I do not think that they will sing to me.

- The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

We have all, surely, scoffed at the tragic demise of a fictional figure. How many iterations of “if I were Orpheus, I would not look back” have been uttered? I personally always believed that if I had an abnormal affinity for red hoods, I would not waste time inquiring after my beastly grandmother’s features. That such fables are brought to us in our unsuspecting youth is offensive, to say the least.

I jest, of course. When we are immersed in the momentum of a story, we do not (generally) question the wits of its cast. Their decisions are the manufacturers of their journey, which is the manufacturer of our story. And I do have an abnormal affinity for stories. If I were a sailor passing through convenient rock formations, I would not think to cover my ears; if the enrapturing song of a siren wanted to make a home in me, I would throw the doors open. Sure, I would just walk through them and into my watery death, but I would have heard some true hits in my final moments.

Except that sometimes the siren does not want to entice a sailor into her depths. Sometimes, the siren wants to be heard and sighted. To be visited, briefly glimpsed, and dispatched. Sometimes, the siren wants to scoff at her role in the story and send you on your way. You will not catch her inert.

Atargatis, Syrian goddess of fertility, is one of the earliest conceptions of the mermaid. Her creation myth sees her flinging herself into a lake in shame and grief after the birth of her daughter, and transforming into a “human-headed fish.” (Fish are specifically regarded as symbols of fertility due to their connection to the sea’s potential for rebirth and transformation.) Atargatis soon became known to the Greeks as the goddess Dercetos and, with her incorporation into Greek mythology, the mermaid figure entered numerous religious and cultural collectives. They’re present in African folklore as Mami Wata, in Japan as Ningyo, and in Slavic mythology as the Rusalka. However, the mermaid cemented its place in popular culture with Hans Christian Andersen’s 1837 fairytale The Little Mermaid. The tale famously depicts a mermaid who falls in love with a human prince and exchanges her voice for a pair of legs, in the hopes that she will be able to walk among other humans and, most importantly, pursue her attraction. Ultimately, after finding her love unreciprocated and her prince betrothed to another, she’s encouraged to murder her prince and return to a life underwater. She is unable to follow through and casts herself into the ocean. She turns into seafoam and, thanks to her sacrifice and her wish to become immortal, she is allowed to perform good deeds until her lifespan comes to an end, after which she will be granted a soul and ascend to Heaven.

Such lovely tales. The 2006 video game Rule of Rose, developed by Punchline, contains a similar storybook, which serves as the introduction to one of the game’s best chapters—and to one of the most wonderfully succinct and devastating levels in video game history.

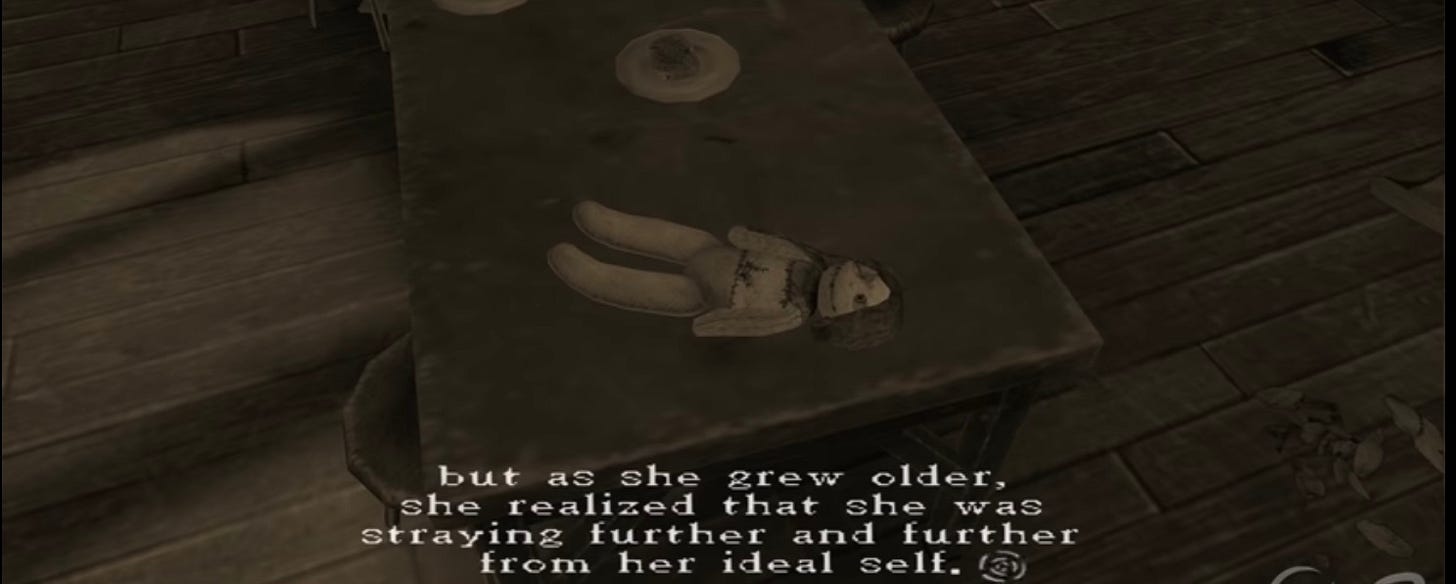

A long, long time ago, the Mermaid Princess fell in love with a human prince.

But for years, her love went unrequited.

Before long, she was old and decrepit, all alone even on the day of her death.

The poor, poor Princess of the Sea Kingdom.

Who'd ever want to become an ugly woman like her?

From the outset, it is clear that “The Mermaid Princess” is not interested in retelling The Little Mermaid word for word. Her mortality, for one, stands as the biggest deviation from Andersen’s story, as the poor princess ages and collects physical mementos of her past years, which are in turn dismissed as ugliness. There is no grand Christian intervention rescuing her from the oblivion promised by death.

Now, for greater context, the overarching premise of the game follows Jennifer, an amnesiac 19-year-old girl who embarks on a journey to recover the memories of her childhood spent at the Rose Garden Orphanage. Given her tenuous grasp on her past, most of the game takes place in an airship more-or-less mapped after the orphanage, where she’s thrust into the Red Crayon Aristocracy—led by the Princess of the Red Rose and her Bear Prince (sigh). The Aristocracy lists all the proper, if slightly inaccurate, ranks, beginning with “Duchess" and ending with "Beggar", where Jennifer is predictably placed. Through the discovery of storybooks, first given to her by a child-sized manifestation of her id, she uncovers the mystery of her forgotten memories. These prove to be turbulent and puzzling, and the game is chock full of euphemisms and allegories to guide us through the slippery corners of Jennifer’s mind, including the abuses she suffered at the hands of her fellow orphans.

Occupying the rank of Duchess, we are introduced to Diana, our titular siren. Diana is a firecracker. Fosforito. She wields smiles as readily as a bladed weapon and only ever uses them to lacerate. Her kindness is a conduit for callousness—it does not exist for much else. As the Duchess, the highest ranking position after the Princess of the Red Rose, she is responsible for carrying out the Princess’s orders, which often veer toward alarming depravity.

But our Princess does not have a monopoly on violence. The aristocrats are a vicious bunch and Jennifer is equally ostracized and harassed by most of them, victimized even by their complicit silences. Diana, in particular, demonstrates a vested interest in her own feats of cruelty. In the trailer for the game, which also serves as the game’s opening, we are invited into one of the only private moments we ever see her in—a character-defining one.

Meg, the Baroness, is hopelessly in love with Diana. This love is innocent, potent with the abandon of youth, and utterly indifferent to the violence that permeates its home. Diana holds nothing but disdain for Meg’s affections and constantly engages in a game to reprove and assuage her for the fault of loving her. More than anything, this sits at the center of her character: Diana lays down a path of roses then collapses its steps while you’re still walking just for the certainty that she can rescue you back up. The sensations shift so drastically you do not even understand what happened, which thrills her greatly, because she is also seeking to understand.

Diana, our Strong-Willed Princess, is eventually revealed to be a victim of the orphanage’s director, Mr. Hoffman. Both her and Clara, an older orphan, are shown to experience extended sexual abuse at his hands, an unbearable state quietly and eerily encapsulated in the Mermaid Princess chapter. Jennifer, up to this point, has endured the perplexing trials of the Aristocracy and is now faced with three fairytales in what I like to call The Promise Trilogy. In order to piece together the memory of her “dear friend,” she must traverse these three stories (“The Bird of Happiness,” “The Goat Sisters,” and “The Mermaid Princess”) and arrive at the heart of their predicament. You’re free to pick any booklet you’d like, but looking at the structure of the finished promise, the trilogy would end with The Mermaid Princess chapter. Let’s talk about mermaids.

Half-Human, Half-Fish: Nature vs. Humanity

Mermaids, with their bisected selves, typically mystify those fortunate enough to encounter them, and so have historically stood for a sense of ambiguity. As Peter Mortensen contemplates in “Half Fish, Half Woman,” “the mermaid’s power to fascinate [...] stems not only from her female gender but also from her uncertain species identity.” This is perfectly transcribed in Diana’s volatility, her swift transitions from a coddling gentleness, to sudden reproach, to an incandescent violence. It’s hard to read her and even harder to predict what her smiles purport to do. As such, she best embodies this fantastical ambiguity rather than the duality of humanity and nature fundamental to the figure of the mermaid. She’s more at home in the chimeric enmeshment of parts, in that distance where you cannot yet distinguish head from tails.

This is due in no small part to her fractured relationship with nature, one corroded by the assumed hostility that the world outside the orphanage represents. The first time the player ever encounters her, she is seen brutally beating a bag with a wooden stick, the contents of which are later understood to be Jennifer’s loyal dog Brown.

Both identities are, at this point, concealed, but it is not necessary to replay the story to conclude that it is an animal inside the bag and Diana underneath the paper bag. Future incidents, such as the mysterious death of Eleanor’s cherished “bird of happiness,” will see her perpetrating violence on animals. Even the Aristocracy’s signature punishment demands the distress of a small rat, who’s made to share its torment with the chosen victim.

In one of Rule of Rose’s favorite fits of irony, Diana’s duties in the orphanage involve looking after Hoffman’s koi fish, itself an externalization of Diana’s animal half. This is the only interaction between Diana and an animal entirely void of violence, only insofar as Diana is the one causing it. Not only is the fish a means of control for Hoffman, who dangles the rewards of obedience and the retribution for naughtiness in front of Diana, but it is also a token of mythologization.

The storybook that prefaces the chapter introduces us to the tragedy of a lonely, mortal mermaid, hardly an image to yearn after. But the chapter itself stages the search for an “unmarried mermaid,” a mythical creature that befuddles the children in its nonexistence.

Concurrently, we are presented with Diana’s despair after losing Hoffman’s fish—and thus, the quest for the weekly gift unfolds parallel to Diana’s harried search for the koi, which she terms her “precious thing.” The two expeditions come to a head in the same room after discoveries of doll and fish parts. From outside, we are faced with an elderly man, a weeping child, and a single bed; inside, with a hanging, mutilated mermaid gaping her mouth at us, suspended over the bed.

A boss fight ensues, scored with the agonizing notes of Clara’s screams and moans. It is long, it is arduous, it is eminently uncomfortable. Clara lunges at you from surprise spots in the ceiling, strikes you when you’re near and spouts what appears to be vomit when you’re far. The battle grates on your nerves and still manages to make the motions of self-defense feel wrong and uncalled for. This is Clara, in pain, flailing her slitted wrists and swinging her stitched-up chest, her smiling, bloodied belly at you. You only hit her so she will stop. She only screams so it will stop.

This is Clara’s abuse unwrapped, brought to the surface in a display of internal and external wounds. It is the crystallization of the scenes you’ve been grimacing at and turning away from, as she disappears for seconds before shocking you back into action, dictating the pace at which you will witness her suffering. It is the eradication of euphemism making room for myth—a myth mangled by its hosts’ realities.

Because there’s more than one reality being represented. Clara, as much as she is her own character, is also an extension of Diana. The chapter opens with Diana and climaxes with Clara, only to return to Diana for its culmination; it is careful to address both, but it also blurs the lines separating them. Clara is Diana’s feared fate. Their fungibility is a testament to the dynamics in an abusive household: abuse is always excruciatingly personal, but when it runs unfettered in a single place, it is not difficult for boundaries, especially those demarcating identity, to become diffuse. Another’s predicament is yours, their flattened autonomy and construction of self evaporating into your own unfinished one. You share the memories so intimately it is unthinkable you will ever share them to each other, ever speak them outloud.

And so the narrative bounces from one girl to another, as they deflect the spotlight and return it to each other. We’ve seen the storybook, we’ve seen Diana trail after her precious thing, Clara trail after her nightmare, thrall to his whims. We’ve seen her transformed and piercingly bare.

Once the fight comes to an end, Clara plummets to the bed as a mermaid doll, the prized gift for the Aristocrats. Jennifer bears witness to Hoffman’s harassment of Diana as he forces a confession out of her and taunts her with a handy “no new mummy or daddy will want you if you look like that.” Then it’s done, and Diana shakes off the ghostly imprint of Hoffman’s hands as if shaking dirt from her clothes, and glowers quite spectacularly at you.

You, standing there holding the doll, because of course. She snatches the mermaid from your grip and inside the tank it goes, a rag imitation of a half-human, half-fish replacing the precious koi.

Diana, mythologized.

The specter of her abuse deals in amputations, in hasty, indelicate combinations of parts. She is both herself and another, child and adolescent, calculating and rash, tender and wounding. Her animal half is captive, domesticated, safe under her watchful eye—and left to roam on its worst instincts (after all, “mariners are not wary only of the mermaid’s feminine wiles; her tail—her otherness, her halfness—presents true peril.”) She is unable to connect with nature in its sincerity, though her vicious understanding of the natural world is sincere enough. She’s the human being on the other side of the tank, the real-world counterpart of the storybook’s decrepit mermaid, looking at herself and wondering why she’s dying.

The only other time we hear of mermaids after the conclusion of her chapter is in the epilogue, when Jennifer reflects on Diana’s desire to become pure and beautiful like one.

This is, I believe, when we finally come to understand the entanglement of Diana’s illusions and self-awareness, as well as the mythologization of her abuse. Boria Sax writes “As a woman, the mermaid is nearly always idealized. She has a beautiful complexion and long flowing hair. She is also privy to secret knowledge, not only of the depths of the sea but sometimes even of the future. Nevertheless, she has little understanding of human beings. She is capricious and inconstant, like the weather itself.” The purity of Diana’s mermaid seems inaccessible to her the older she gets, a feeling compounded by Hoffman’s sexual abuse, her developing body, and her increasingly violent responses to her circumstances. Her mermaid promises a state of absolute accomplishment where the future is no longer uncertain, but to reach her she must step into that future, and the future is cordoned off by squalor.

Abuse has the inexhaustible capacity to make you feel blemished and ruined; Diana has been raised in an isolated culture of cleanliness, which is obedience, which is goodness, which is the stairway to Merland. It is no coincidence that the Mermaid Princess’s tail is made of wound rope—much like the other objects furnishing the airship-orphanage, rope is used as both a tool of entrapment and control, and as a means to conceal and bury instances of recurring violence. Keeping clean is keeping quiet, and Diana’s ticket out of here is paid for in pristine silence.

This impossible ideal feeds its tendrils to the Aristocracy’s required gift, as well as to the conflicting images of Clara’s less-than-fantastical transformation. Their nonexistence and devastation cannot both be possible. The aristocrats, as previously mentioned, balk at the prospect of procuring an “unmarried mermaid,” as no such thing exists. But what of Diana, wandering the halls in search of her other half? What of Clara and her downcast gaze, avoiding any pair of eyes that could discern her plight? The storybook closes, reads “I am yours, even in death,” and Jennifer remembers, swears to never forget.

Pivoting back to the motif of animal cruelty, it seems germane to mention that the actual mermaid doll is implied to be Meg and Eleanor’s doing. Slice Hoffman’s fish in half, sever a doll’s pair of legs, and you’ve ranked up in the orphan hierarchy! None of the characters are above inflicting pain on living creatures in order to get ahead or, really, to indirectly harm each other. Diana excels at this for most of the game.

However, while far from being the only character who participates in such acts, Diana’s pattern of violence targets that which escapes her understanding: the sprawling natural world outside the drab walls of the orphanage, Eleanor’s escapist attachment to her little red bird, and, perhaps most glaringly, Meg’s devoted love for her. The latter provides a window through which we can gaze at Diana's internal struggles with her own human nature.

Make the Goat Eat It: Diana & Queerness

The cultural shift around popular depictions of the mermaid has come to view her as a queer symbol. Through that characteristic bifurcated identity, the boundary separating human and animal is erased and so mermaids challenge “social divisions of class, race, and identity.” Adrienne Rich’s 1973 poetry collection, Diving Into the Wreck, references mermaids in rather ambiguous language, interpreting them as an “androgynous being” with “fluid pronouns.” The mermaid has become a figure of diversity, no longer a preying creature of halved identities but a celebrated symbol of consolidated experiences, of self-affirming and self-asserting communities.

However, Diana’s circumstances and the unorthodox imposition of a mermaidian identity curtail the potential for a queer breakthrough. Diana not only discards but attempts to consume Meg’s declarations of love by making the goats (one of whom represents Diana herself) eat the heartfelt missive. In her introductory scene, she exerts a calculated degree of bodily autonomy by raising her dress and offering femininity as a form of identification, stopping just short of titillating but continuing just enough to evince pain.

The subject of Diana’s bandage is highly disputed (or at least it was in the defunct mystery forums for the game/still is in my mind), but its presence is no mistake. The two most likely culprits are a) self-harm and b) damage to the pelvic area as a result of rape. Whatever the answer (an equally calculated mystery), Diana’s deliberate revelation suggests a coupling of sexuality and pain (it is also argued that Diana’s nursing of Meg’s wound in the trailer is a display of hypersexuality. I generally agree.) But as we’ve learned, Diana is deeply terrified of the changes wracking her body, both leans into and withdraws from the femininity of her presentation. In another subversion of the mermaid’s radical symbolisms, she seeks to produce discomfort in others not out of a well-rooted confidence, a perfect consummation of humanity and nature, but out of an existential discontentment with both.

So what of poor, spurned, sweet Meg? Well, in the aforementioned trailer, Diana does what she does best. She weaponizes desire, indulges the orphans’ wildest dreams of acceptance then turns their claws on them, all in the spirit of standing beatifically over their writhing, desperate bodies. None of these rapidly changing behaviors come at the behest of the Princess of the Red Rose—they’re all idiosyncratically Diana.

Desire is not an embodied quality but an externalized process, a state other people are suspended in and waiting to be excised from. Look at her behavior with Meg. They sneak around in bathrooms (sites of shameful intimacy and taboo conversations, anyone?) Diana tenderly relieves Meg’s pain by bringing her inside of her body, Diana feigns complete, boldfaced ignorance at the disappearance of Meg’s love letter (having tore it in half herself) then consoles her once Jennifer is successfully framed. I must emphasize: she tried to feed it to the goat. Her schtick reeks of repression! She’ll freely accept Meg’s wounds and tears, but her affections are to be fed to another of her animal counterparts, to no avail. That love, so eagerly gifted, has nowhere to be hidden, except maybe behind her clueless smile.

Don’t Look in There! Fertility & Pregnancy

As posited in the history of the mermaid, her position as a symbol of fertility is a basic tenet in her mythology. “She represents fertility, understood not as having children [she has them rarely] but the enormous power of the ocean to generate unknown forms of life.” Instantly, we can surmise that Rule of Rose is once again challenging the traditional role of the mermaid in popular culture. The threat of pregnancy hovers over Diana day and night; it is not merely a transference from abstract power to solid representation. Looking closely at the Mermaid Princess boss design, we can make out a line stitching Clara’s belly closed, hinting at a surgical procedure—the projectiles of vomit during the fight further support this suggestion. Likewise, Clara’s frantic refusal to let Jennifer peek into one of the drawers in the Sick Bay and the raised pads on the hospital cots she is later seen scrubbing all point to a terminated pregnancy. It is not that “sexual intercourse between man and mermaid is not easily imaginable,” but that in the Rose Garden Orphanage, imagination is forced to supersede reality. The physiological norms by which mermaids exist hold that they cannot copulate with humans, but here, where the mermaid is simultaneously a synthesis of abuse and a fabled role model, she is beholden to the biological consequences of sex. Pregnancy will lurk as long as Hoffman does; that mythical bottom half has been sliced off and thrown into a tank. Diana has even evaded the legacy of her namesake, that of a certain Roman goddess. Virginity is but a taunt and she will never watch over childbirth, nevermind over the safety of a mother.

(One of the game’s most haunting and easily missable moments takes place when you try to open the Sick Bay drawer against Clara’s wishes. Jennifer will vehemently refuse.)

You’ll Be a Mermaid Too!

At the end of the Promise Trilogy, Jennifer pieces together her oath to Wendy: “Everlasting true love, I am yours.” Throughout their individual quests, Eleanor, Meg, and Diana stress the importance of their “precious thing,” beloved tethers that echo Jennifer’s own precious vow. Eleanor’s red bird encases the promise of happiness, Meg’s letter the promise of love, and Diana’s fish. Mhm. It’s hardly hers, really more of a burdensome task than a cherished pet. I would argue that her troubling fish promises safety. The horrific, bloody endings of each of the girls’ treasures forebode a worse fate for Jennifer’s promise, but they also individually betray the loss of the children’s dreams. The bird, the letter, the fish—these are all frail hopes the girls secretly guard, and they all meet their untimely end at each other’s hands. As Wendy, our sly Princess of the Red Rose, eventually epitomizes, the girls are unable to tolerate being alone in their misery. They must trap and bind each other to ensure not obedience but solidarity. No matter how diametrically opposed these concepts are, they lack the means to tell them apart. This is the (hierarchically organized) bed they made and they will not lie in it alone—they’re so far removed from the rest of the world and so desperately playing at reality.

Diana, most tragically of all, is stunted by her metaphors: mythical in the obfuscations of her abuse and painstakingly real in its reverberations. A mermaid in captivity, not even permitted the radiance of an underwater kingdom. “Their sexuality is supposedly free and easy, yet to know them is impossible. They exist in an idealized world [...] Like the undersea world imagined by Andersen, it is soulless and beautiful.” But Rule of Rose does not allow Diana to remain unknowable. In one of her unused dialogues, Diana monologues about mermaids, finally vocalizing her aspirations firsthand.

Each and every girl becomes a mermaid! You'll be a mermaid, too. A new daddy will come for us and we'll all be mermaids. Mr. Hoffman said I'd be a beautiful mermaid. And the king of Merland will come for me.

Sure, cut content is not necessarily “canon”, but this is Rule of Rose, a game defined by its mysteries and interpretations. I am taking the creative liberty to expand the meaning of “canon.” Diana verbalizes her rosy dreams of dissolving, pointedly equating “becoming a mermaid” with “being adopted,” relying on Hoffman’s verdict of her future, mermaidian beauty. Humbert Humbert’s “parody of incest” is pervasive in this excerpt and inescapable in the nuclear family model that allows Hoffman to abuse Clara and Diana with impunity. Orphanages are distinct from traditional households in that they’re both a pitstop in the way toward proper family integration and strive to offer a family structure to its children, in a myriad of poor ways. Diana, Hoffman says, will complete her transition to mermaid when she’s finally adopted; the King of Merland will come for her. But in the Aristocracy, all children are princes and princesses, and Martha, the only adult besides Hoffman, is deemed a queen. The hierarchy is already in place, the children hyper aware of the rank they occupy regardless of weekly gift compliance. Diana, Jennifer shows us, is already a mermaid, languishing under the abuses of her father figure. Any narratives to the contrary, any transference of responsibility tacitly threatening future suffering, are all null.

How does Diana defy her role? Yes, she is an abused child exhibiting trauma responses, but she is also a self-aware teenager conflicted by her illusions, her body, her life of contrariety. She imagines and daydreams like all the others, and exists beyond those fits of cruelty (though they are the reason I love her so dearly.) She externalizes the violence inflicted on her. She does not draw you under the waves for an eternity of rapture, but for a temporary retreat into her psyche, for a disconcerting reenactment of her suffering, viewed in another. Almost like she’s studying the stitching in her design. She fails as a siren, constantly rejects the symbols of her predecessors and houses them all at once. She’s under threat of fertility, not an abstract symbol of it; she’s awfully vulnerable to sex, not above its possibility. She does not reflect anyone’s temptations or longings, doesn’t speak on behalf of the sea. Her state as a mermaid is personal, intimate. She will not live forever, which is lucky. She will not reside in a soulless and beautiful place; the place Jennifer’s memories have made for her is an expanse of light, only as beautiful as she was real.

Till human voices wake us, and we drown.

This is probably the first essay I’ve ever written for myself outside of academic restrictions. Please let me know what you think!